Six lessons from Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis

Tldr: do the right thing. Especially when you don't feel like it.

Religion is an underrated technology for becoming a less awful human being.1 This is unfortunate, because in my peer group of secular, urban-dwelling, university-degree-thumping, VC-funded-snack-eating peers, it’s usually not well understood or respected.

I often find myself explaining that Buddhism and Daoism are less so religions, and more just philosophies for life that try to create less hellish outcomes. They also have some fun characters (Siddhartha, Guanyin), interesting social rituals, and some cool costumes and buildings - much like Star Wars2. ☸️☯️🌌⚔️

Christmas seemed like a good time to dig into…well, Christianity. And for a fledgling like myself who’s just getting her theological sea legs, Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis was a great way to begin.

Here is what I’ve learned.

1. There is such a thing as goodness

“The Moral Law does not give us any grounds for thinking that God is ‘good’ in the sense of being indulgent, or soft, or sympathetic. There is nothing indulgent about the Moral Law. It is as hard as nails. It tells you to do the straight thing and it does not seem to care how painful, or dangerous, or difficult it is to do […] there may be no sense in asking it to make allowances for you or let you off, just as there is no sense in asking the multiplication table to let you off when you do your sums wrong […]

You may want Him to make an exception in your own case, to let you off this one time; but you know at bottom that unless the power behind the world really and unalterably detests that sort of behaviour, then He cannot be good.”

-Lewis, p. 30

One idea that I’ve always struggled with in Buddhism and Daoism is the common interpretation that everything is subjective. We call something good, and in doing so we render other things bad. It is our desperate clinging to these constructed “categories” that drives our suffering, our rage, and our wars.

The aim of these two religions is to be aware of our brain’s constant desire to put things into boxes, to stop doing so, and thus to stop doing the dumb and hurtful things that are required to maintain those boxes. This is how we transcend suffering:

When people see some things as beautiful,

other things become ugly.

When people see some things as good,

other things become bad.-Tao Te Ching, verse 2

But Lewis makes an extremely simple point that I have trouble refuting: if this is true, then why do we humans get so upset when awful things happen?

“Whenever you find a man who says he does not believe in a real Right and Wrong, you will find the same man going back on this a moment later. He may break his promise to you, but if you try breaking one to him he will be complaining "It's not fair" before you can say Jack Robinson […] if there is no such thing as Right and Wrong- in other words, if there is no Law of Nature-what is the difference between a fair treaty and an unfair one? Have they not let the cat out of the bag and shown that, whatever they say, they really know the Law of Nature just like anyone else?”

-Lewis, p. 6

The Ravi Zacharias sermon that I mentioned in my last essay also references a passage from Orthodoxy by G. K. Chesterton - famous for his defense of fences:

“For all denunciation implies a moral doctrine of some kind; and the modern revolutionist doubts not only the institution he denounces, but the doctrine by which he denounces it […]

In short, the modern revolutionist, being an infinite skeptic, is always engaged in undermining his own mines. In his book on politics he attacks men for trampling on morality; in his book on ethics he attacks morality for trampling on men.

Therefore the modern man in revolt has become practically useless for all purposes of revolt. By rebelling against everything he has lost his right to rebel against anything.”

-Orthodoxy by G. K. Chesterton

I have to admit - they’ve got me on this one. 🤔

2. Faith is not blind belief: it is the basis of free will

I have always struggled with the idea of faith. It is commonly defined in our secular circles as believing in something, despite there being no proof for it. (Never mind that this is how venture capital works 🙄)

I have also always struggled with the idea of original sin. If God is so perfect, then why did He create people capable of sin? The Jehovah’s Witnesses who came around to our house as a kid didn’t do a very good job explaining this one - at least, not in terms that a six year old could understand3.

Again, Lewis had an extremely simple and compelling answer for this one:

Why, then, did God give them free will? Because free will, though it makes evil possible, is also the only thing that makes possible any love or goodness or joy worth having. A world of automata--of creatures that worked like machines--would hardly be worth creating…

Of course God knew what would happen if they used their freedom the wrong way: apparently He thought it worth the risk.

-Lewis, p. 48

And thus Christianity reconciles itself with the Dao. Yes, absolute goodness exists. But it is a person’s freedom to choose the opposite - and the choice not to do so - that makes goodness meaningful at all.

Lewis then throws down this incredible definition of Faith:

“But supposing a man's reason once decides that the weight of the evidence is for it. I can tell that man what is going to happen to him in the next few weeks […] there will come a moment when he wants a woman, or wants to tell a lie, or feels very pleased with himself, or sees a chance of making a little money in some way that is not perfectly fair: some moment, in fact, at which it would be very convenient if Christianity were not true […]

Now Faith, in the sense in which I am here using the word, is the art of holding on to things your reason has once accepted, in spite of your changing moods.

That is why Faith is such a necessary virtue: unless you teach your moods 'where they get off', you can never be either a sound Christian or even a sound atheist, but just a creature dithering to and fro…”

-Lewis, p. 140

A common objection against organized religion - or having moral principles of any kind, really - is that they seem to be very inconvenient for freedom.

This opinion isn’t entirely unfounded. Indeed, folks try to co-opt religious doctrine to uphold sexism, homophobia, or any number of other freedom-denying practices in the name of “morality”. I’m all for being on constant guard for this anti-human nonsense and calling bullshit when you see it.

But Lewis contends that without faith, we are just “creatures dithering to and fro” - and it’s hard to argue with this. Without belief in some higher, invariant goodness, we are not free at all - but simply hostages to worse masters than God. Pride, rage, lust, fear…all the usual suspects.

Lewis has defined faith as the ability to stick to previously accepted reason, despite every emotion and instinct in our body screaming otherwise.

In other words, faith is what separates us from mindless balls of animal instinct - and is therefore nothing less than free will itself.

3. The strawman version of religion is pretty stupid

Another myth that abounds in secular interpretations of Christianity is that God is something like an unelected, judgmental jerk in the sky, meting out punishment and forgiveness in the same way that a small claims court doles out fines or rewards.

Lewis has a few things to say about this:

“Such people put up a version of Christianity suitable for a child of six and make that the object of their attack.

When you try to explain the Christian doctrine as it is really held by an instructed adult, they then complain that you are making their heads turn round…”

-Lewis, p. 41

Much like piano or ballet lessons, religion is one of those things that is forced upon children who have little say in the matter. It’s often done more to indulge a parent’s ego than to promote a kid’s well-being. This usually causes fierce resentment, and they don’t learn a damn thing.

Also like piano or ballet lessons, religion is hard to appreciate until you’ve lived a while - and then all of a sudden you wish you had gotten into the whole game earlier. You have to see some ugly things to realize that it’s worth doing the hard, hard work of creating beautiful things instead.

But hey. No time like the present. 🎹🩰🛐

4. Forgiveness is not something that can be given or withheld: it is the natural consequence of understanding

So if God isn’t doling out red cards and penalty kicks like the world’s most capricious, high stakes soccer referee, then what exactly is God’s forgiveness?

Lewis has a lovely answer for this too. It is the corollary of true repentance - no more and no less4:

“Laying down your arms, surrendering, saying you are sorry, realising that you have been on the wrong track and getting ready to start life over again from the ground floor — that is the only way out of a “hole.” This process of surrender — this movement full speed astern — is what Christians call repentance […]”

And Lewis makes it very clear to us that God won’t be fooled by anything less than the real deal. In fact, He literally cannot:

“Remember, this repentance, this willing submission to humiliation and a kind of death, is not something God demands of you before He will take you back and which He could let you off of if He chose: it is simply a description of what going back to Him is like. If you ask God to take you back without it, you are really asking Him to let you go back without going back. It cannot happen.”

-Lewis, p. 57

Very well, so that settles the issue of how I go about getting God’s forgiveness for my sins. But what about the hard task of forgiving other people? Lewis has an answer for this too:

“For a long time I used to think this a silly, straw-splitting distinction: how could you hate what a man did and not hate the man? But years later it occurred to me that there was one man to whom I had been doing this all my life—namely myself.

However much I might dislike my own cowardice or conceit or greed, I went on loving myself. There had never been the slightest difficulty about it. In fact the very reason why l hated the things was that I loved the man. Just because I loved myself, I was sorry to find that I was the sort of man who did those things.”

-Lewis, p. 117

And let none of us bear any illusions that we aren’t this sort of person, because…

5. If you fancy yourself a good person, you’re doing it wrong

Another common objection to organized religion is that they can sometimes be a self-righteous bunch. Lewis agrees that this is no bueno:

“The trouble begins when you pass from thinking, 'I have pleased him; all is well,' to thinking, 'What a fine person I must be to have done it.”

-Lewis, p. 126

And the reason you’ll never be this fine of a person is because…

In God you come up against something which is in every respect immeasurably superior to yourself. Unless you know God as that – and, therefore, know yourself as nothing in comparison – you do not know God at all. As long as you are proud, you cannot know God.

A proud man is always looking down on things and people: and, of course, as long as you are looking down, you cannot see something that is above you.

-Lewis, p. 124

6. You will always fail, and that’s why it’s worth doing

So if God isn’t a megalomaniacal small claims court judge in the world’s best selling fiction novel, then what is He?

At the very least, I think He is a metaphor, and an archetype. We humans have been trying to figure out how to beat each other up less brutally for thousands of years. Stories have always been a compelling way to do this.

God is our way of conceptualizing a perfect love that can never be achieved, but is absolutely worth striving for. He embodies a way of being that, if practised by everyone, would render society a wonderful (dare we say, Heavenly? 🙃) place to live.

And we don’t even have to get it right all the time. In fact, we certainly won’t.

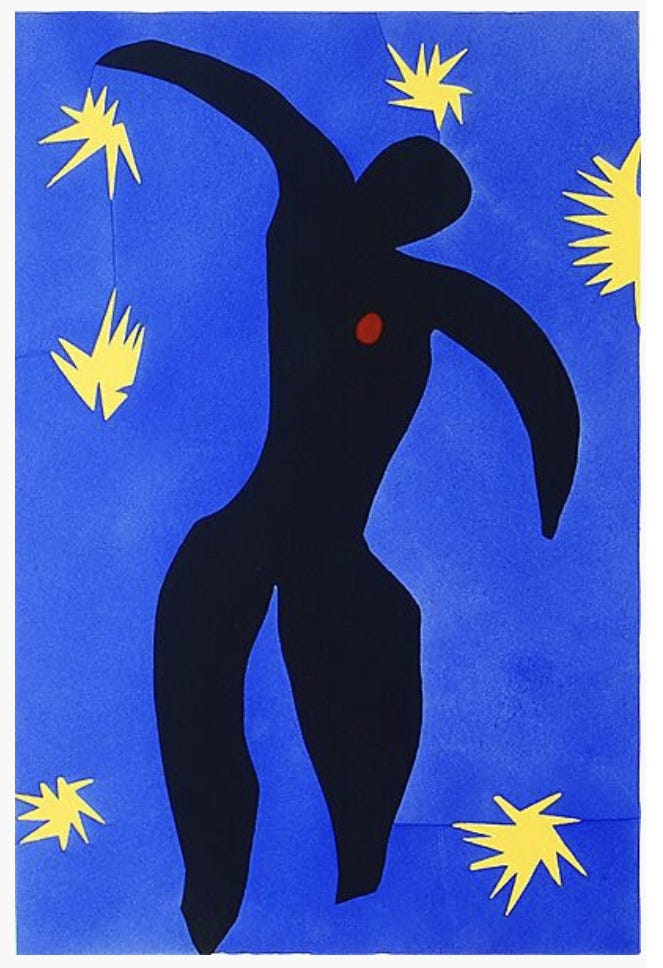

Many of us look at an impossible task and deem it Sisyphean - something like a never-ending disappointment:

Lewis’ Christianity flips this idea on its head. The fact that we will never live up to God’s perfect ideal is both liberating and meaningful. Liberating, because it means we can stumble but always get ourselves back on track. Meaningful, because it means that we will always have something to strive for.

Every little bit counts, and nudges the world a touch further away from hell. Anyone who’s ever seen that little spark of divinity in someone else knows what I am talking about. The grey world as we know it splits open and something infinite peeks out, for the briefest of moments. But it is blinding, beautiful, and unmistakable:

“Already the new men are dotted here and there all over the earth […] Every now and then one meets them. Their very voices and faces are different from ours: stronger, quieter, happier, more radiant. They begin where most of us leave off […] They will not be very like the idea of ‘religious people’ which you have formed from your general reading.

They do not draw attention to themselves. You tend to think that you are being kind to them when they are really being kind to you. They love you more than other men do, but they need you less. (We must get over wanting to be needed: in some goodish people, specially women5, that is the hardest of all temptations to resist.) […]

When you have recognised one of them, you will recognise the next one much more easily. And I strongly suspect (but how should I know?) that they recognise one another immediately and infallibly, across every barrier of colour, sex, class, age, and even of creeds.

In that way, to become holy is rather like joining a secret society. To put it at the very lowest, it must be great fun.”

-Lewis, p. 223

Gratitude

Thanks go to:

Ben Parry, for suggesting Mere Christianity as a holiday read 🌟🎄

Joe Perkins, for juxtaposing Buddhism and Christianity as “technologies” for alleviating suffering 💾 🙏

Arnab Chatterjee and Chris Masurek, for entertaining my WhatsApp rants on the topic despite my knowing -10,000 things about theology 🤷🏻♀️

One could raise the usual protests: what about Catholic priests who abuse children? The Spanish Inquisition? Missionaries, smallpox, being just awful to gay folks who want to get married, etc. I think these things tear down Christianity as an institution as much as Bayer and DuPont and Lehman and lobbyists tear down the institution of capitalism. Nobody denies that these outcomes are awful. But we also live in a world where where the ideas of respect for private property - and forgiveness - have gone viral, and these things are no cultural accident. One has only to look at countries where these ideas don’t reign to realize how valuable these ideas are.

You could get into angry online pissing contests over what is and isn’t canon, and gatekeep what it means to be a true “fan”, but that’s really missing the point.

Also, the Tao Te Ching is obviously just a massive ripoff of The Force 😉 :

“He who is in harmony with the Tao

is like a newborn child.

Its bones are soft, its muscles are weak,

but its grip is powerful.“

Which, according to some quote widely (mis)attributed to either Feynman or Einstein, means they didn’t understand it themselves. 🙃

As opposed to buying indulgences or paying “fines”, which Lewis (and most of us) would argue entirely misses the point. You can’t be DuPont or McKinsey, factoring the settlement into your discounted cash flow analysis while still maintaining the full set of mental machinery that led to harmful outcomes in the first place. That may check the FDA’s boxes, but it won’t check God’s.

At first blush this comes across as some classic 1950s sexism, but I think Lewis actually touches on a deep truth here. There’s a reason why behaviours that tend to be labeled “effeminate”, “needy”, or downright pathological in men can pass as regular romantic behaviour in women (read: the lyrics of literally any Taylor Swift song). By and large, I think society still conceptualizes male self-actualization as professional success, while conceptualizing female self-actualization as the ability to secure a romantic bond - at any cost.